Introduction

When the technology of paper arrived in the West, specifically Western Europe during the 12th to 14th century, people were skeptical and hesitant to accept it into their daily lives. It was disregarded as a useful technology and thought of as dirty or undesirable due to its material origins and cultural associations. However, with printing press technology rising to popularity in the 15th century, so did the cultural need for paper, and thus recognition of its usefulness and ultimately acceptance. From the onset of this cultural adoption of print and paper, as paper was primarily made from old rags, Western Europe experienced ongoing chronic rag shortages in attempts to support this developing print culture.

Ragpickers fulfilled a vital role during this crisis that empowered the abilities of the printing press in Western Europe from the medieval period up to the 19th century, without whom the success of print culture would not have been possible. This paper will illustrate the ragpicker’s foundational cultural impact through interpreting their contributions that sustained the paper industry, their role in empowering printers and the printing press, and their power behind ensuring the success of print culture. However crucial the role, it was one that was generally regarded as wholly unsavoury and utterly contemptible, sometimes called rag-men or women, rag-rakers, rag-gatherers, or rag-collectors as other titles for their work (Craig 1). The ragpicker’s contributions established a steady supply of raw materials for paper mills, and in turn, set papermakers up to provide a steady supply of paper for the print culture across Western Europe.

The Essentiality of the Ragpicker

To better understand the essentiality of the ragpicker’s role in Western Europe, first we need to establish the common process and needs of the technology of papermaking. Manufacture of rag paper demanded the natural raw materials, primarily flax, to go through several stages and treatments before it was ready to be made into rag paper. For white linens, the first of these treatments included a very time consuming and labour intensive bleaching method called the “old Dutch method” used to turn the raw flax fibers white (Craig 3). Following this bleaching, the fibers would be spun into fabric, and then passed through various usable stages as textile products until they became worn rag scraps ready for papermaking. Heidi Craig details the life cycle of these white linens:

A bed sheet would be used, laundered, and mended over and over again. When it wore out to the extent that it could no longer be used as a sheet, the cloth would be repurposed as wiping rags – for household and bodily uses, such as cleaning cloths, toilet paper, and menstrual cloths – and once more used and laundered again and again. Once the wiping rags themselves became too weak and tattered to be serviceable, they would be put out for collection (Craig 3).

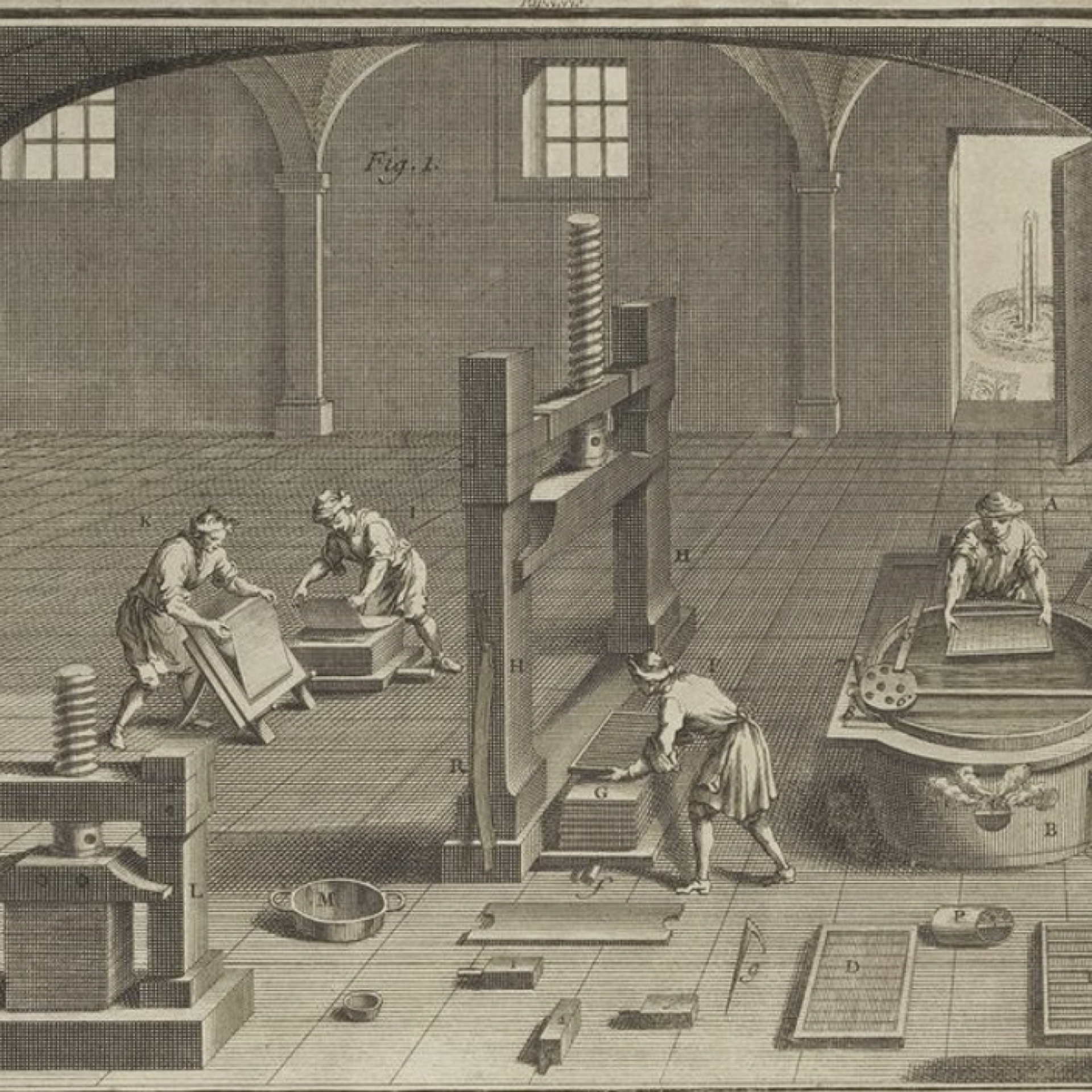

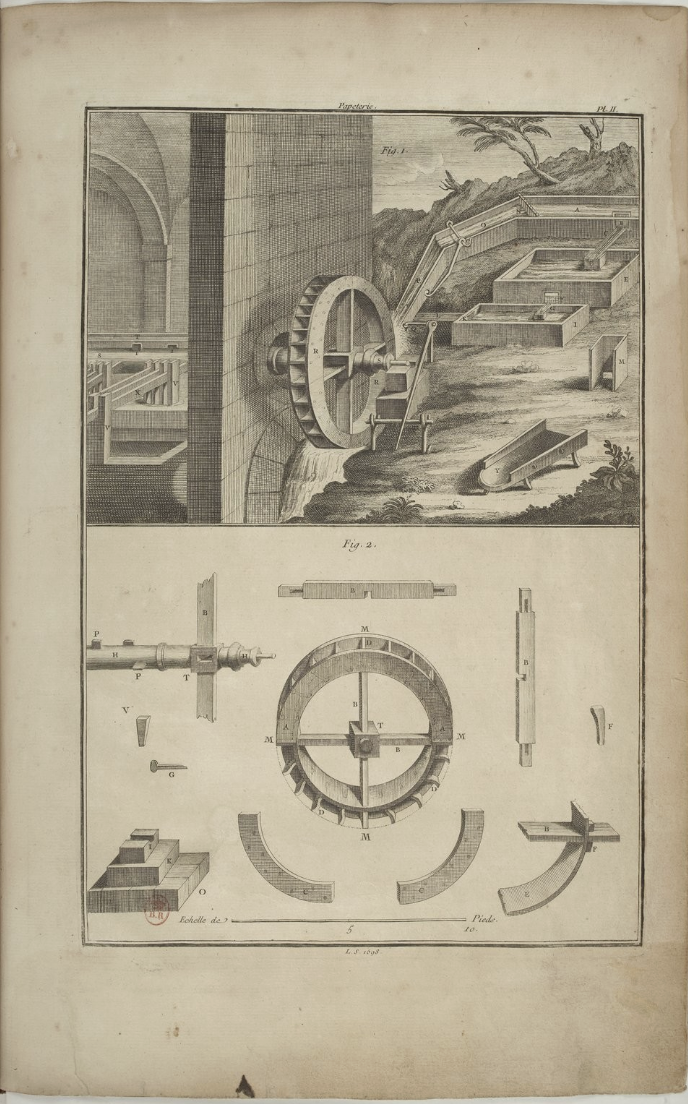

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10671841/f171.highres |

Author: Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande Title: Fig. 1 & Fig. 2 from l'Art de Faire le Papier Description: Diagram of water-powered paper mill Date: 1761 Location: France Medium: Printed monograph, book |

These old scraps, once rendered useless for service as a textile, simultaneously came to their greatest usefulness as a commodity for paper manufacture (Craig 3). They were collected by ragpickers for recycling and sold to the paper mill where a different type of ragpicker sorted through the incoming rags for the creation of various papers (Cardinale 10). Once sorted, the rags were then cut up, cleaned, sanitised, retted, macerated, and made into a pulp bath, to be formed into sheets of paper by papermakers (Watt 29). The resulting sheets were subsequently pressed, dried, sized, pressed and dried again, given smoothening finishing treatments, and then packed into reams to be sold and distributed (Kittler 9).

The ragpicker fulfilled many stages necessary in the transformation of rags from textile to paper. They embodied a role that connected the two industries yet, however pivotal, it was far from a glamorous one. Although there is limited in-depth knowledge about rag picking, we know their days began early at three to four o’clock in the morning (Cardinale 24), combing through urban refuse, dung heaps, and going from home to home in search of tattered textiles to purchase in exchange for other small items like needles, thimbles, or coins (Craig 3). During the later part of their day, these essential labourers would sort through what they had picked and collected to sell to rag dealers or paper manufacturers (Cardinale 24).

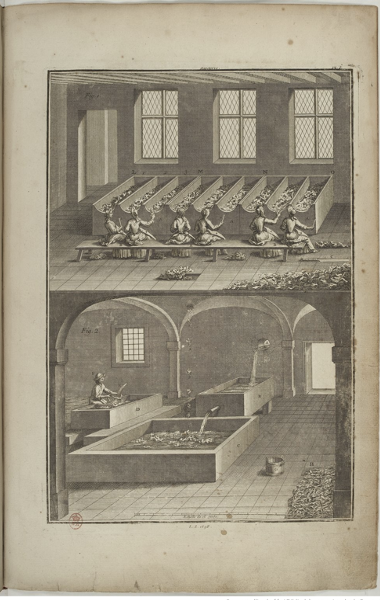

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10671841/f169.highres |

Author: Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande Title: Fig. 1 & Fig. 2 from l'Art de Faire le Papier Description: Diagram of the sorting, washing, and cutting of rags in paper mill Date: 1761 Location: France Medium: Printed monograph, book |

The tasks of the ragpickers employed at the paper mill looked a little different to the ragpicker scavenging in the streets. They instead spent their days at the mill preparing the rags to undergo the transformative process, skillfully sorting by attributes of usable condition, material, purity, strength, and colour, as well as removing seams and notions like buttons, hooks (Cardinale 16; Craig 3; Watt 19).

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/55757/images/i_b_023.jpg |

Author: Alexander Watt Title: Fig. 3 from The Art of Paper-Making Description: The cutter takes her place in front of an oblong box Date: 1890 Location: London, United Kingdom Medium: Printed book |

For the paper, as well as the printing industries, the role ragpickers fulfilled was vital while their marginalized position in society highly benefited the industries. As vulnerable low-class workers, their efforts to make ends meet was commonly exploited. They received just a few pennies per pound despite their productive and tireless services in supplying an invaluable commodity to an ever growing social and cultural starvation for rags and paper (Cardinale 10; 28). This exploitation was very economical for the papermaker in many ways, and consequently too for the printers who purchased their paper. The impact of supplying paper mills with raw material would have been significantly more costly without the ragpicker fulfilling the role on their own accord in the streets and in the factories (Cardinale 28). It allowed the paper mills to receive cheaper local raw material at a low expense and less hassle, as manufacturers did not have to source the materials themselves or find individuals to hire to do so (Cardinale 28). As the hunger for rags became more intense due to the continual rise of the printing press and print culture, paper manufacturers across Western Europe looked to import rags from France or Italy to keep up with the insatiable demands (Cardinale 10). The services provided by local ragpickers reduced the economic burden on the paper industry from the need for expensive importation motivated by the rag shortage.

The significance of rag collection to developing Western European society, culture, and industry brought about interventions from ruling powers to support the paper industry. Early in the Western paper industry, ruling powers in Venice, Italy had granted monopolies on rag collection within the entire Venetian state territory to paper manufacturers in Treviso, to support their own rag picking and paper industries by 1365 (Kittler 14). Later in the growth of the industry, Venice became a treasure trove for ragpickers as it was one of the largest urban centres of late medieval Europe. It produced some of the largest quantities of old rags desired for papermaking (Kittler 14), while the remaining majority of the West only managed to produce a limited supply themselves. Due to this, countries who were less domestically prosperous in this commodity, such as England and North America, relied on rags from Venice to supplement their low local supply in the form of importation, but also attempts to smuggle it across borders (Kittler 14). In England, the crisis prompted Parliament interventions created to redirect as many cotton and linen rags as possible towards managing the crisis. The Act for Burying in Woolen of 1666, and subsequent revisions through to 1680, “required the dead (except plague victims and the poor) to be buried in pure English woolen shrouds, forbidding use of linen or foreign textiles as grave clothes” (Craig 3). The rules and regulations that quickly became directly involved in improving rag picking returns, displays the significance of the service ragpickers provided to the paper and print industries and culture in Western Europe.

Ragpickers Empowering the Printing Press

The value of the collection of rags and paper manufacture in facilitating and enriching print culture was also endorsed by the printing industry as well, only further highlighting the ragpicker’s necessity and indicating the cyclical patterns of these connected businesses. After the introduction of newspapers into Western print culture, the severity of the crisis intensified, and printers were desperate (Haynes 73). Members of the industry, such as booksellers and printers, included advertisements for purchasing old rags from readers in their newspapers and books (Skeehan 688). Printers depended on the services of the ragpicker because they supplied not only the raw material to create the medium they worked with, but ensured a slow yet steady supply of it due to their efficient and diligent work. This was important for the success of a printmaker’s edition of prints as it allowed them to avoid both excess stock as well as insufficient availability of paper (Kittler 13).

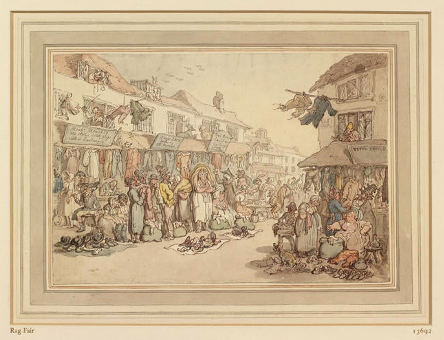

|

Author: Thomas Rowlandson Title: Rag Fair Description: A watercolour of a bustling street scene. Men and women have set out stalls selling second hand clothes ranging from breeches to boots. Date: c. 1800 Medium: Pen, ink, watercolour over pencil Dimensions: 18.4 x 27.1 cm |

With the rising print culture dispensing increasing quantities of various products from printers and the printing press such as books, newspapers, broadsides, pamphlets, brochures, bills, and other paper-based media, there was an equally rising demand for both white and brown paper and all grades in between. Ragpickers were able to source various raw materials to supply this range of grades of paper to printers. Quality white linen rags were of highest value and used to create fine white writing and printing papers, while lower quality textile scraps like canvas, hemp, sails, and rope, were used to create other coarser cheaper grades of papers, sometimes mixed with additional rags as needed (Craig 3; Watt 19). Cotton held a middle ground providing the ability to produce a range of grades of paper, efficiently, and at a relatively low cost (Cardinale 13). The white linen rags used to manufacture the valuable fine white papers could be found in dung-heaps, and therefore did not literally result in perfectly white paper, but creamy or grey-toned (Haynes 73). The value of these linen papers derived from the high quality textile rags, which produced paper that was both supple and possessed excellent felting and strength qualities, in order to bear the extreme pressure of the printing press while remaining receptive to ink (Davidson 254; 258). Printers desiring the cheapest paper were those printing newspapers, whose main concern was not the quality of the paper, but rather the cheapness and quantity, so long as it was suitable enough to be printed on (Haynes 73). Ragpickers working in the streets provided a powerful contribution to the manufacture and availability of the assortment of paper grade options to printers, as they were willing to diligently perform the unsavoury work which empowered the success of printing operations.

Ragpickers and Print Culture

With the continual developments of paper and print weaving itself into the economy and society, Western Europe came to heavily depend on the labour of ragpickers, whose role became increasingly foundational as their cultural impact grew. Ragpickers facilitated a swell of cultural enrichment through their role in ensuring the success of print culture and its intersection with improved affordability, education, employment, and the economy.

Prior to paper in the West, parchment and vellum was the commonly available writing medium of choice, which was greatly expensive due to the nature of the material requiring the costly raising of cattle and sheep to produce it (Hoffmann). Paper on the other hand, was a more reasonable price for everyday use, up to over six times cheaper (Kittler 19). With paper coming into play in various grades, it was made available to a larger range of people, directing written correspondence and communication, together with education, to become more accessible. Hence too, the ability of ideas, knowledge, and histories could be more easily recorded and shared to a larger audience (Hoffmann). These conveniences operated in a cyclical nature which only encouraged and enhanced each other. As a result of the acceleration of affordable paper and print culture, Western European societies were provided with an inflation in levels of commonplace education. This was only possible with the labour of the ragpickers providing the foundation of paper and print’s cultural production.

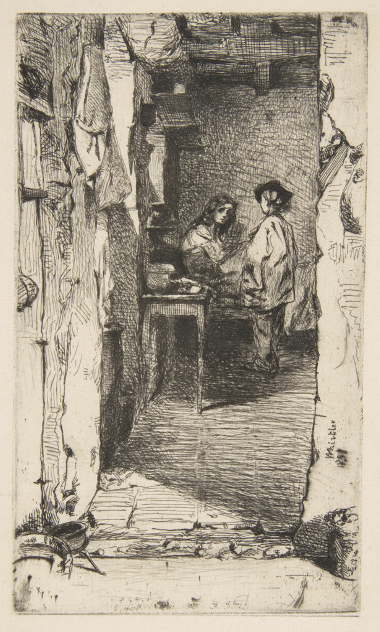

https://media.nga.gov/iiif/aac45f62-6f10-4548-899b-1b216ead68f8/full/!588,600/0/default.jpg |

Author: James McNeill Whistler Title: Rag Pickers, Quartier Mouffetard, Paris Date: 1858 Medium: Etching and drypoint in black on wove paper Dimensions: 21.59 × 14.29 cm |

Rag picking additionally provided employment opportunities for a greater number of impoverished individuals, who would have otherwise been worse off with begging as their only alternative to scrape for income. Marginalized members of society, mainly immigrants, women, and children, were able to productively employ themselves and their time on the streets, performing work towards the economy and social stability that was still seen as honest and indispensable, in spite of their exploitation, or be employed at paper mills in the rag room (Kittler 17; Cardinale 18). I would like to briefly highlight the role of child ragpickers and their contributions to the success of print culture. Children were commonly exposed through daily life interactions with peddlers, ragpickers, and print media, the value and role of the ragpicker in papermaking and their industrial economy (Cardinale 10). Print media such as instructional, vocational, and educational story books and pamphlets, familiarized and encouraged rag picking as a respectable employment alternative to begging (Senchyne 550-551). It was a culturally suggested avenue of work that was cautioned as “more a last resort than a first choice”, but one destitute urban children could perform that was still above begging due to the potential productivity and contributions towards society (Senchyne 550-551). Though they were children, their labour was meaningful and not unimportant in ensuring the success of print culture and the economy.

|

Author: Édouard Manet Title: The Ragpicker Description: The Ragpicker represents one of the practitioners of a now-obsolete profession that involved sifting through the detritus of daily life—not only rags, which were sold to paper manufacturers—but also kitchen scraps, soap and other castoffs that were left out for trash collectors. Date: c. 1865-1870 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: 194.9 x 130.8 cm |

Conclusion

Many quickly developing sectors and features of Western European society depended on the skills of the ragpicker from the medieval period up to the nineteenth century. They carried out grim tasks in efforts to reap what could be collected of textile scraps that were no longer domestically useful and therefore put out for collection, or discarded in urban rubbish and waste matter. Ragpickers played an indispensable role in aiding the industry’s struggle to produce sufficient quantities of paper for print. With the extensive incorporation of paper and print culture in society over the centuries, Western Europe became reliant on the ragpicker’s contributions to maintain social stability. The ragpicker’s essentiality only further strengthened during this period, as they sustained print culture and the paper industry, ensuring its success.

Sabrina Ly

Sabrina is a queer Chinese-Canadian multidisciplinary artist who is currently based and studying in Toronto, Ontario. Their experience as an artist began in 2016 studying a wide range of disciplines at Bealart forming the multidisciplinary foundation of their practice. Sculptures, installations, and other three-dimensional constructions featuring the use of digital media, glass, stone, wire, paper, textiles, and ceramics have dominated their body of work with recent interests extending to leather and bookbinding. Through experimental approaches across different mediums, their works discuss themes of process and inquiries into lived experiences alongside topics of memory, history, mental health, and relationships. In recent works, the fabrication process continues to contribute to an essence of their work, exploiting the poeticism of an honest process in an attempt to enrich the materiality and sensuality of their work as a love letter to the subject of each piece.

Cover image: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10671841/f190.item

Cardinale, Corrine. “A Penny for Your Rags: Rag Pickers and the Paper Industry in the Later 19th Century.” University at Buffalo, 2018.

Craig, Heidi. “Rags, Ragpickers, and Early Modern Papermaking.” Literature Compass, vol. 16, no. 5, May 2019, pp. 1–11. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12523.

Davidson, Paul B. “Any Old Rags to Sell?” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 69, no. 4, 1949, pp. 254–61.

Haynes, Williams. “Oldest Material: Newest Uses.” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 76, no. 2, 1953, pp. 71–76.

Hoffmann, James J. The Spread of Papermaking Technology into Europe. https://go-gale-com.ocadu.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=toro37158&id=GALE%7CCX3408500877&v=2.1&it=r&aty=ip. Accessed 9 Apr. 2024.

Kittler, Juraj. “From Rags to Riches: The Limits of Early Paper Manufacturing and Their Impact on Book Print in Renaissance Venice.” Media History, vol. 21, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 8–22. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2014.955840.

La Lande, Jérôme de (1732-1807) Auteur du texte. Art de Faire Le Papier , Par M. de La Lande. 1761. gallica.bnf.fr, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10671841.

Senchyne, Jonathan. “Rags Make Paper, Paper Makes Money: Material Texts and Metaphors of Capital.” Technology and Culture, vol. 58, no. 2, 2017, pp. 545–55.

Skeehan, Danielle. “Texts and Textiles: Commercial Poetics and Material Economies in the Early Atlantic.” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 36, no. 4, 2016, pp. 681–700.

The Ragpicker c. 1865-1870 Édouard Manet. https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/. Accessed 24 July 2024.

Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) - Rag Fair. https://www.rct.uk/collection/913692/rag-fair. Accessed 24 July 2024.

Watt, Alexander. The Art of Paper-Making A Practical Handbook of the Manufacture of Paper from Rags, Esparto, Straw, and Other Fibrous Materials, Including the Manufacture of Pulp from Wood Fibre. 2017. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/55757.

Whistler, James McNeill. Rag Pickers, Quartier Mouffetard, Paris,. etching and drypoint in black on wove paper, 1858.