This work is inspired by Lithuanian folklore and Chela Sandoval’s chapter “U.S. Third World Feminism- Differential Social Movement I” in Methodology of the Oppressed (2000).1 While researching Lithuanian folklore, it became clear that many themes in these folkloric tales are misogynistic in nature.2 With Sandoval’s theories in mind, I have re-written these stories with a feminist lens.

Sandoval’s theories of differential consciousness stood out to me as the most significant game-changer in terms of feminist thinking. Humans are complicated, we all live such diverse lives. Broadly, Sandoval points out that resistance can only ever come from various subject positions and lived experiences. How can one person speak for everyone and how can one strategy of resistance be the end game for all groups of marginalized peoples? Therefore, movement is critical and learning from each other is crucial because it allows people to live the lives they choose to live. This movement and respect for people’s knowledge inspired this story below. Through fantasy and folklore, I explore how differential consciousness can aid in improving normative social structures.

Foreword

The Raganos provide an exciting perspective in Lithuanian folklore. The Raganos are feared, rejected, misunderstood, used, and at the same time, needed. Their placement on the exterior of villages aids in their powers and their different forms of knowledge. Ragana means “the seeing” and they are healers of ailments. Even though they help their communities, they are blamed when anything goes wrong. One of the Raganaos’ powers is being able to transform into animal form. This allows for an understanding of the forest creatures' needs and desires. As Raganos are not consistently in animal form, they are aware of their position in society and how to best be an ally for the forest creatures and women. Cast aside by the village, the Raganos bridge together the forest dwellers and the villagers.

Audra the Ragana

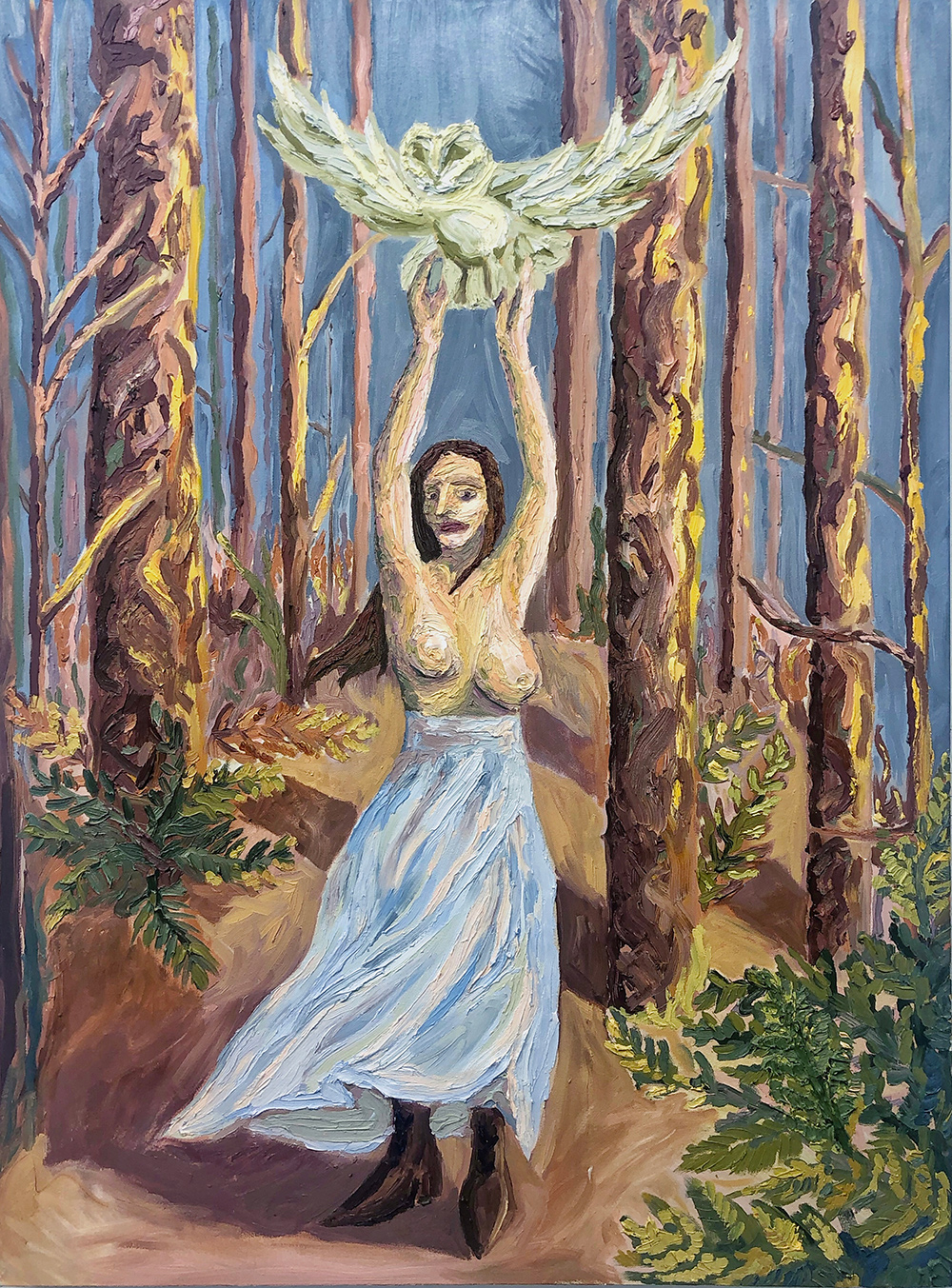

This story is about Audra, the Ragana. Audra was born in the village. She had a father, a mother, and two brothers; she was the youngest. She was cast aside from the beginning as she was perceived to be strange. Her verbal communication skills were slow to develop, and she continually stared and spooked people with her intense gaze. People compared her to that of an owl zoning in on prey. Audra’s stern forehead, deep-set eyes and hooked nose didn’t help her case. As she continued to develop throughout puberty, her body took an unusual turn. One breast developed quickly and incredibly large, whereas the other one never developed. People often made fun of her, telling her she would never have a suitor come to rescue her, her white lily would stay intact forever, and she would never be granted the privilege to birth the next generation of the village. To avoid these comments, Audra would run away to the forest.

Audra never understood why the villagers were so afraid of the woods. She thought the forest was magical. The trees seemed to dance with her, swaying so gracefully to the songs of the wind. The animals, forest creatures and devils, seemed to gravitate to her, and she was able to communicate clearly with them. This communication and connection were beyond what words could describe.

Over time, Audra pondered why the young girls of the village thought that they needed to be saved by suitors. She didn’t see why bearing children was a privilege, especially to birth a baby into this village. Here, the men praise their women, how they are so crucial to the health of the village, how their maternal skills guide the village with a feminine touch. This all sounds nice, but actions speak louder than words.

Husbands rarely treated their wives with kindness or as equals. The women’s job was to be domesticated like the wild animals the men stole from the forest. The men loved their alcohol more than the women, and as they all consumed so much, it was considered normal. It was typical to sing your wife’s praises, but then go home and beat them to release life’s frustrations or rape them so they will produce more children - hopefully, male heirs. The husbands were not the only people to fear in a marriage, the mother-in-law was a whole other game to navigate. It seemed that the mother-in-law wanted the wife to experience the same hardships she did, to continue such bad treatment into the future. This difficult life as a woman is what happened when she fit in the system, imagine what would happen to others deemed to not fit in. Audra learned quickly that she wanted nothing to do with this system, she was proud that she would never have a suitor or birth children. This seemed like more of a privilege than to continue on in the ways of the generations of women before her. With this realization of dislike for village life, she ran away and created a home for herself at the edge of the woods.

Audra soon learned that she had powers of communication with all living things and quickly learned about a new world. Plants and herbs would share which ailments they could fix. The forest creatures were knowledgeable about how to continually evolve to create a better living situation in the woods for everyone. They all wanted to keep the balance of the forest and its society by maintaining respect for each individual being. Many of the animals that gravitated to her were other Raganos in animal form, and they generously shared their knowledge. Audra’s animal form was an owl, which signified power and knowledge. This gave Audra pride in her human appearance. Her large singular breast meant to other Raganos how powerful Audra could be. She could be a leader; she could help the villagers and forest dwellers to coexist. To do this, she would need to gain the trust of the villagers and help them understand how to treat everyone fairly and with respect, to learn and listen to one another, and to break the vicious cycle of pain being passed down through the generations. Society needed to be healthier for humans and creatures alike.

Medeina, the forest mother, planted information in the village about the magical healing powers of Audra. No ailment was too large or small for her to mend, and it wasn’t long until the first villager came seeking Audra’s help. The first woman asked for birth control options because she no longer wanted to fall victim to their husband’s persistent attempts for male heirs. Next came a young girl who was embarrassed about losing her virginity in a passionate encounter with a soldier. She needed to appear as though she had not lost her white lily so she wouldn’t be disowned. The women kept coming. Once they had been so mean to her, and now they needed her magical powers: valerian root to make their husbands pass out, salves to mend bruises, herb concoctions to perform abortions and spells to keep suitors away.

Now that the women trusted Audra, Medenia released the next stage of the plan. It was clear from the outside that the village women needed to talk to each other and start chipping away at the structure of their village society. If no one but the men were happy, then things needed to change.

The forest was once in a state of turmoil too. The devils had supreme powers to guard the forest from the greedy humans, who, on their own, would take all the animals and plants. The devils vowed to never let any humans enter the forest again. The forests beings did not like the devils. Truth be told, they were a little scared of them and treated them as outcasts. The forest ferns had magical powers that kept the forest floor and the villagers healthy and were loved by all. The ferns grew in abundance but soon became so thick they were choking and dying. They needed the villagers to harvest the leaves, but the devils would not let them enter. The forest beings didn’t know who to support and had many discussions. Finally, the forest society recognized that the ferns and the devils were both critical in maintaining the well-being of the forest. After much deliberation, they asked the devils to step aside on the shortest night of the year to allow the harvesting of the leaves while limiting the villagers’ greed. To gain agreement, they started treating the devils as equals in their forest society while recognizing their supreme powers in guarding the forest.

Audra started talking to the women, conversations that began to uplift the village women. More and more came to discuss strategies and Audra shared her point of view with them. “We must demand that we are equal to men! If we can’t have jobs, then our job of raising families must be accounted for!” one woman shouted. That’s when Audra suggested that every being was equal to each other. Even down to the little Kaukai that villagers dismiss as being lifeless dust bunnies. In fact, these creatures enhance the love and warmth in the homes of the villages. These little friends need respect for the value they bring. No more being thrown out in dustpans.

“Equals?? Pfft! We are not equal. These men are garbage!” another woman countered. As women kept shouting out their opinions, the room became divided. Everyone thought their idea was the best and was unwilling to see where the others were coming from.

Audra was surprised at how stuck these women were in their ideas. Since living in the forest, Audra witnessed such beautiful flow of differing opinions and viewpoints and finding a way to use the best of everyone/everything for the health of the forest. The forest could not remain healthy if each forest dweller maintained one stagnate viewpoint.

Audra realized that by getting these women to talk openly about their issues and ideas, her job of planting seeds and getting a revolution started in the village had begun. Now she could step back and let these women figure out how best to tackle their situations.

It wasn’t long after that one night when Audra heard knocks at her door. Once her eyes adjusted to the dark, she was confused by the band of men standing together outside. All ages, genders, races, who inhabit the villages were standing in front of her, needing her help. They were sick and frustrated: they were ill from drinking too much, they were disappointed that fewer children were being born, and they were frustrated that they couldn’t understand the women’s new demands for living. “Audra, please help us and guide us, like you did for the women in the village. We have been cast aside by our women, and we no longer want to be second-class citizens. We want to be able to live our lives in the best way we can, free from frustrations and sickness.” And with that, she invited the men into her home and treated them with medicines and words of wisdom on how to better their village without exclusion of any one being. Audra was hopeful for the future when everyone in the village and forest, could meet again, despite their differences.

Ragana, Katrina Kuras, Winter 2019, 3ft x 4ft, oil on canvas

Katrina Kuras

- Sandoval, Chela. “U.S. Third World Feminism- Differential Social Movement I.” Methodology of the Oppressed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. 40-63.

- Maria Paplauskas-Ramunas, “Women In Lithuanian Folklore” DC53788. Doctoral disseration of Philosophy, Ottawa University. 1952