On September 11, 1973, General Augusto Pinochet led the Chilean National Army with the support of the United States government to La Moneda Palace to overthrow the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. The coup d’état set in motion a tumultuous 17-year dictatorship ruled by violence, censorship, and the implementation of neoliberal economic policies. In response to the human rights violations and the pervasive state terror, Chilean shantytown women, the arpilleristas, began depicting the horrors and daily life under the regime through brightly coloured patchwork pictures, arpilleras. The arpilleras became a form of political protest under a brutal dictatorship that incorporated a rich history of textiles and weaving and acted as receptacles for memory and documentation, resistance to state violence, and created alternative economies under neoliberal policies. The collective work of the Chilean mothers and lack of singular authorship emphasizes the community trauma expressed in the arpilleras, and points to the ubiquity of violence experienced nationally.

This paper examines arpilleras as feminist interventions against state terror and the collective process of both the reclamation and making of memory. The arpilleristas emerge from, and reflect a socialist history precipitated by the election and subsequent coup of the democratically elected Allende government. By expressing a shared trauma of the violence and repression of the dictatorship, the arpilleras materialize into the locus of community-based initiatives led by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad. The subject of many of the arpilleras sought to confront the world stage by representing what was being censored and rendered invisible by the state. The clandestine nature of the arpillera workshops and the constant collective re-living of trauma created a catalyst for community-based organization that permitted protest that did not explicitly put the arpilleristas in direct endangerment. Along with the socialization of shantytown women and mutual support amongst the community, the arpilleras formed an alternative economy which critiqued neoliberalism while producing sites of memory.

The years leading up to the 1973 coup d’état were marked with extreme tension between the National and Christian Democratic Parties, after Popular Unity leader Salvador Allende did not receive the majority in the 1970 presidential elections.1 Despite a backroom deal between the National Party and the Christian Democratic Party to block Allende’s presidential election, Allende gained an electoral majority and won the 1970 election.2 After assuming the presidency, Allende enacted socialist economic policies to revive the economy which included a nationalization program involving the major banks, iron, coal, and copper mines, and land reforms that expropriated Chilean latifundia from hacienda owners.3 By 1972, the economic expansion carried out by Allende’s policies was halted due to lack of investment by capitalists and the U.S. blockage of foreign loans which inevitably lead to a period of economic crisis.4 The Opposition parties took this opportunity to justify their increasingly militant actions, and the eventual 1973 coup d’état. It is important to note that during Allende’s presidency, the policies enacted benefitted the working-class citizens of Chile which resulted in a growing class consciousness and organization of a group of people who have been historically exploited and neglected.

The September 11th coup d’état initially began with the coup plotters, the golpistas, who replaced all pro-Allende broadcast media with martial music and military correspondences. Radio Magallanes, a radio station run by the Chilean Communist Party was the only one broadcasting its own programming by the mid-morning.5 At 9:00 AM, Radio Magallanes delivered Allende’s final address to the nation where he implored the citizens of Chile to remain strong despite the impending collapse of the democratic government.6 Shortly after Allende’s broadcast, the Chilean Air Force began bombing La Moneda, and Pinochet’s junta entered the palace where Allende died. Following the coup d’état, the Junta dissolved Congress, suspended the constitution, along with political rights, and installed a military regime headed by General Augusto Pinochet.7 Throughout this period, Pinochet established the Chilean secret police, the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), which enacted the dictator’s extreme suppression of opposition through the forcible disappearance of subversives and by censoring media and artists.8 During the first few weeks of the military regime, extreme violations of human rights were implemented, including the infamous “Caravan of Death”, where Pinochet sent a Chilean Army death squad to execute Marxists and supporters of Allende. In addition to the eradication and subordination of the people of Chile, Pinochet implemented neoliberal policies that eliminated price controls, opened up trade to international competition, encouraged exports and privatized public services.9 Although all Chilean citizens were affected by the policies and terrors of Pinochet’s regime, Chilean women were disproportionately disadvantaged because their male family members were disappeared, as well, their primary sources of income.

In 1973, the Vicaría de la Solidaridad was formed by the Catholic Church to help women in shantytowns who were experiencing extreme levels of poverty due to the growing number of desaparecidos and lack of resources to provide for their families. One of their initiatives was the establishment of community industries and workshops which included arpillera workshops (taller), as well as other services like soup kitchens and neighbourhood health centres. Through the Vicaría, shantytown women could create arpilleras that expressed the trauma their communities were enduring while earning an income to support their families. Jacqueline Adams, a researcher and sociologist at the University of California at Berkley explains “The Vicaría recruited into the workshops shantytown women were having difficulty feeding their families because their husbands were unemployed. As well as being poor, these women were the victims of intense repression: shantytown raids by the military, water and electricity cuts, and periodic roundups of their family members.”10 Despite government suppression of the creation and distribution of arpilleras, the Vicaría exported them to nongovernmental and human rights organizations in Europe and North America, who would in turn sell the arpilleras to the public.

The arpilleras were instrumental in disseminating information about the realities of life under the Pinochet regime because they retold and memorialized events of state terror that were otherwise censored on the world stage. The Coup (1986) (Fig. 1) created by arpilleristas E.M and F.D.D is an arpillera that commemorates the September 11th, 1973 coup d’état. The embroidered and patched arpillera measures 15x19.75 inches, and features the presidential palace engulfed in flames with soldiers approaching the front entrance of the palace with their guns drawn. Above the palace are two fighter jets approaching the burning palace, while a helicopter hovers above. The most prominent element of this arpillera is the stark contrast between the stitching around the figures, and the stitching around the flames coming out of the palace. The arpilleristas notably used different cuts of textiles and elongated stitches to denote the ferocity of the flames, which in turn creates a sense of dynamism that adds to the level of anxiety when viewing this arpillera. Adams describes the importance of the infusion of emotion into the arpilleras, “These arpilleras work at an emotional as well as cognitive level. The images are moving, and the Vicaría directed the women to produce arpilleras that would pull on people’s heartstrings”.11 While the events surrounding the coup were known to most of the world from the Pinochet regime, the interpretation of the events from local women demonstrates the grief of citizens.

Another example of the documentation of the state’s violence is Disposal of Bodies into the Sea (n.d) (Fig. 2), which depicts the bodies of the desaparecidos being dumped into the sea. The 16x19-inch arpillera features a group of women standing on the road looking up in horror at a helicopter that is dumping bodies out into the sea. This arpillera is particularly important because it operates as evidence of the crimes that DINA and other Chilean intelligence agencies were vehemently trying to deny.12 People who were deemed “subversives” were captured, imprisoned in clandestine detention centres, tortured, killed, and then dumped into the sea to destroy any evidence of their presence in the hands of the intelligence agencies. The “disappearing” tactic enforced by the Pinochet regime was merely an appropriation of the Nazi’s Gestapo strategies to instate perpetual fear and subordination of the nation to prevent revolutionary movements. According to Carlos Huneeus, a Chilean professor and diplomat, approximately 93.9% of the victims of human rights abuse and political violence during the Pinochet regime were male.13 Along with the uncertainty of the whereabouts and fate of their male friends and family, the women left faced the ostensibly insurmountable role of primary caregivers while trying to survive under intense scrutiny of the regime. It is worth noting that one of the “laws of the arpillera” as per the Vicaría employees, was that “the arpillerista could only depict something she had experienced, not something imaginary”, proving the reality of the disposal of the desaparecidos that the government refuted.14 The shared experiences of the shantytown women laid the foundation for the careful organization of political protest under the guise of the arpillera.

The arpilleras functioned as receptacles of memory and the wounds of Chilean history, but they also served as a means of collective organization for the mobilization of women and community-based projects. Adams argues that “Initially, the point of the workshops was to help the shantytown mothers earn an income. Before long, however, some Vicaría employees realized that they could use the arpilleras as a way of socializing the women” pointing towards a social cohesion of the women through the arpilleras.15 The joint venture of the women secretly creating arpilleras to represent the pain and suffering they collectively felt opened up a safe space among communities to remember, grieve, and resist together. Community Arpillera Workshop (1976) (Fig. 3) demonstrates the organization of the shantytown women who work collectively in and outside of the arpillera workshop. The 15x19 inch arpillera depicts a shantytown with four houses and an arpillera workshop in the left bottom corner. The women outside of the houses carry bags or textiles, while others hold papers and perform household tasks. Whereas the viewer can only see the outside of the houses, the interior of the workshop reveals a group of arpilleristas who work together to sew and patch together an arpillera. This example denotes the collective work of women, even with the strict ban on the production and distribution of arpilleras under the dictatorship. By creating arpilleras, the women can engage in political action without having to face the same risks if they were publicly congregating and protesting. Eliana Moya-Raggio points out the significance of the arpilleras for the mobilization of Chilean women, “Housebound and isolated in the past because she was both poor and female, she now moves from passive observer to active participant in a process of collective work that not only helps her in feeding her children, but also changes her life radically, giving her a clear goal…”16 Just as much as the arpilleras were a feminist intervention and venue for mutual healing, they also generated alternative economies under Pinochet’s neoliberal policies.

Upon establishing the military dictatorship, Pinochet introduced a number of neoliberal economic reforms which were meant to legitimize the regime under the guise of economic success. The new economic program was created with the help of a group of economists known as the Chicago Boys, who received their moniker due to their education at the University of Chicago.17 The economic reforms were meant to primarily benefit the big-business community and employers with a focus on the exportation of natural resources. In addition to prioritizing private interests, the economic reforms saw the privatization of previously public services like the pension system and the electric power system, along with major cuts to public education, health and housing services.18 As a result, access to vital public services for lower income groups was severely curtailed and led to high unemployment, a drop in real wages, increased poverty and income inequality.19

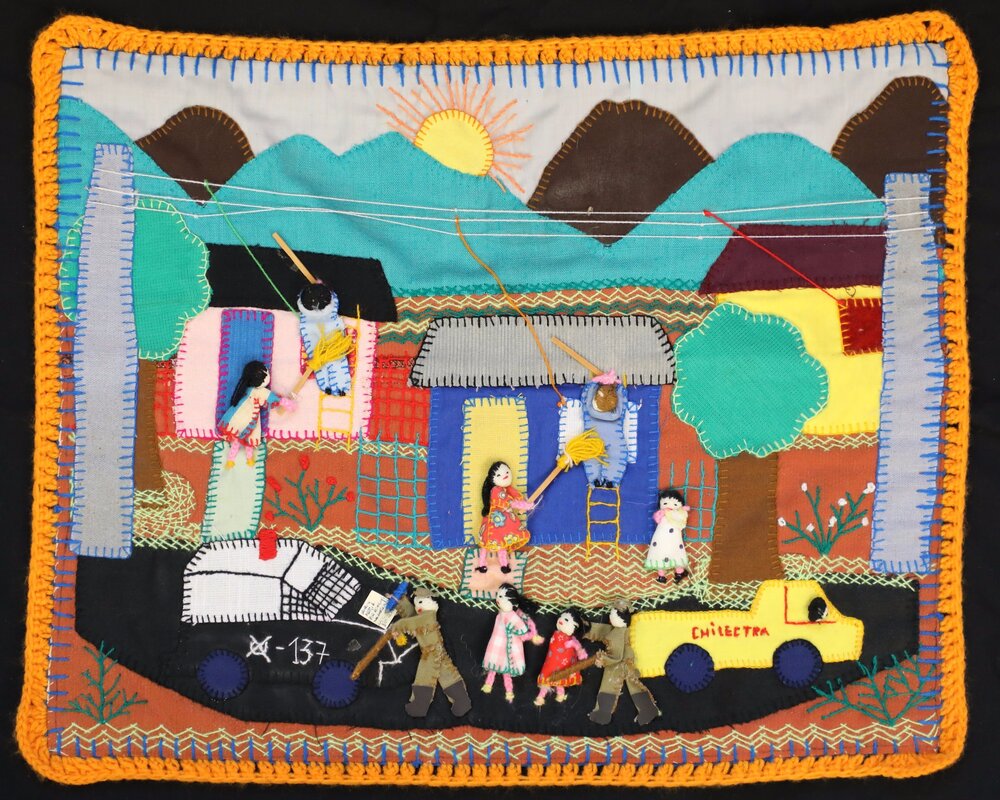

Chilectra Disconnecting Power Lines (1976) (Fig. 4) represents the gravity of the neoliberal policies enforced by Pinochet’s regime, and their disastrous effects on low income communities. The 15x19 inch arpillera depicts women siphoning electricity by hooking cables to Chilectra power lines, as two police officers arrest two women in the foreground. Beside the police officers is a Chilectra truck, suggesting the complicity of the electric company in the oppression of low-income communities and the poverty that occurs in them. Arpilleras in this regard serve as a response to unemployment and a way for women to support their families during economic crisis. As previously suggested, the establishment of arpillera workshops by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad was primarily motivated to provide income for struggling women in shantytowns, however, the structure of the workshops and the ways in which money was allocated to the members redefines arpilleras as a viable alternative economy. Acting as intermediaries, the Vicaría sold the arpilleras to various human rights organizations internationally, to tourists and to Chilean exiles who expressed solidarity with the shantytown women. Because of the clandestine nature of the operation, the arpilleras had to be smuggled out to avoid seizure from officials or DINA spies. Writer and artist Betty LaDuke explains that following the sale of the arpilleras, “Each woman receives her full payment, apart from 10% which is kept as a common group emergency fund.”20 This ensured the longevity of the arpillera workshops, and paid for the necessary expenses to purchase materials and additional services like soup kitchens. While arpillera workshops remained active well into the 1990s, the political undertones and depictions of state violence slowly began to disappear to make way for brightly coloured and happy scenes, signifying the end of Pinochet’s military dictatorship and the Vicaría’s increasingly commercial and conservative orientation.

The arpilleras trace Chilean history through the reimagination of a form of textile work as a vehicle for political protest and for the storytelling of the wounds of Chile during the Pinochet regime. In spite of heavy government censorship, countless human rights violations and pervasive state terror, the arpilleristas documented state violence, collectively subverted the military dictatorship, and created alternative economies under devastating neoliberal economic reforms. The memory work of the arpilleras recall the horrors of the Chilean dictatorship that devastated and displaced tens of thousands of Chileans. The echoes of the arpilleras reverberate through the 2019-2020 Chilean protests. While the protests began in Santiago when students organized a fare evasion campaign in response to increased public transport fares, the protests have expanded and transformed to address the crippling effects of the neoliberal system in place since the Pinochet dictatorship. The Chilean protests and the demands of the citizens carry on the lineage of resistance that began with the shantytown women in the arpillera workshops, which attest to the essence of defiance and memory.

Figure 1: E.M and F.D.D, The Coup, embroidered textile, 15x19.75 inches, 1986, Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

https://molaa.org/arpilleras-online-sept-11

Figure 2: Disposal of Bodies into the Sea, embroidered textile, 16x19 inches, n.d, Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

https://molaa.org/arpilleras-online-aftermath

Figure 3: Community Arpillera Workshop, embroidered textile, 15x19 inches, 1976, Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

https://molaa.org/arpilleras-online-resistance

Figure 4: Chilectra Disconnecting Power Lines, embroidered textile, 15x19 inches, 1976, Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California

https://molaa.org/arpilleras-online-aftermath

Aggie Frasunkiewicz

- Kay, Cristobal, “Chile: The Making of a Coup d’Etat,” Science & Society 39, no. 1 (Spring 1975): 3-25, p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kay, p.4.

- Spener, David, “A Song, Socialism, and the 1973 Military Coup in Chile,” in We Shall Not Be Moved/No mas moverán (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016): 17-26, p. 17-18.

- Ibid.

- Winn, Peter, “The Pinochet Era,” in Victims of the Chilean Miracle: Workers and Neoliberalism in the Pinochet Era, 1973-2002 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004): 14-70, p. 19.

- Ibid.

- Huneeus, Carlos, “The Many Faces of the Pinochet Regime,” in The Pinochet Regime (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2006): 1-30, p. 8.

- Adams, Jacqueline, “Art in Social Movements: Shantytown Women’s Protest in Pinochet’s Chile,” Sociological Forum 17, no. 1 (Mar. 2002): 21-56, p. 30.

- Adams, “Art in Social Movements,” p. 34.

- Ensalaco, Mark, “A War of Extermination,” in Chile under Pinochet: Recovering the Truth (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999): 69-97, p. 87-88.

- Huneeus, “The Many Faces of the Pinochet Regime,” table 1.2, p. 6.

- Adams, “The Makings of Political Art,” p. 342.

- Adams, “The Makings of Political Art,” p. 326.

- Moya-Raggio, Eliana, “Arpilleras: Chilean Culture of Resistance,” Feminist Studies 10, no. 2 (Summer 1984): 277-290, p. 278.

- Huneeus, Carlos, “The Chicago Boys: Legitimation Through Economic Success,” in The Pinochet Regime (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2006): 271-306, p. 271.

- Huneeus, Carlos, “Privatization: The Economic Policy of the Authoritarian Regime,” in The Pinochet Regime (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2006): 307-355, p. 307.

- Davis-Hamel, Ashley, “Successful Neoliberalism?: State Policy, Poverty, and Income Inequality in Chile,” International Social Science Review 87, Issue ¾ (2012): 70-101, p. 83.

- LaDuke, Betty, “Chile: Emboideries of Life and Death,” The Massachusetts Review 24, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 33-40, p. 38.