This inaugural collection of student work for The Arts & Science Review, Writing in Extraordinary Times, originated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic when the university went entirely online. Students finished their coursework while either travelling home as borders closed or already under lockdown. Routines were upended, daily life stressful, and the future uncertain, yet OCAD students persevered in their commitment to think and write about art, design, and culture. The following twelve essays celebrate this commitment. Selected by an editorial committee composed of professors Maria Belén Ordoñez, Kathy Kiloh, and Dot Tuer from submissions nominated by LAS/SIS professors for assignments completed during the 2020 Winter semester, the essays engage topics in contemporary art history, visual culture, philosophy, and critical theory. In making our selection, the committee was attentive to the resonances that emerged amongst the papers, and mindful that the collection was intended to reflect writing for assignments produced during the onset of the pandemic. Funding from the Faculty for writing awards also enabled the committee to select three of the contributors’ essays, one each from Visual Culture (Thomas Boeckner), Humanities (Ada Bierling) and Social Sciences (Alondra Ruiz-Hernandez), to receive a $100 cash prize. We found that the most compelling papers shared synergies that coalesced around themes of contagion, pleasure, consumption, queerness, equity, social justice, and Indigeneity. With these diverse perspectives and affinities in mind, we have grouped the texts into two thematic sections on the body and feminist killjoys.

The first grouping of essays focuses on the body, in its sexual, sensual, and emotional manifestations, as consuming and consumed, with connectives between joy, anxiety, and risk. In a pandemic, bodies are agents of contagion spreading and containing disease in proximity and distance with others. In the texts, bodies are envisioned as material and immaterial objects of desire and containers of identity, subject to and resisting the biopolitics and neoliberal ideologies of an interconnected global world. The second grouping of essays focuses on ways of knowing and seeing the world that approximate Sara Ahmed’s notion of “Feminist Killjoy” in The Promise of Happiness (2010). Ahmed describes feminist killjoys as active disruptions of the “unhappy ones”: the outcasts, queers, racialized, and Indigenous peoples of a global landscape who "kill joy” by not conforming to discourses of positivity premised on being accepted into colonial, patriarchal, and racist systems of knowledge. In the texts, feminist killjoys are at once personal and political, challenging dominant power dynamics and gesturing towards an understanding of joy realized through sensations, speculations, reflexivity, and sites of observation.

The section on the body begins with Thomas Boeckner’s “Untitled: The Representation of Memory and Transmission in the Art of Félix González-Torres,” which is an examination of the Cuban artist’s conceptual interrogation of capitalist consumption and AIDS commemoration. Undertaking an analysis of several of González-Torres's iconic untitled works, Boekner offers a timely reflection on how love, desire, and embodied pleasures become daring and critical gestures when the world finds itself in the grips of a pandemic.

Greta Hamilton’s “Absence in the Body Performances of Ana Mendieta” speaks to intergenerational and social contagion, examining how colonial and misogynistic violence “infect” Mendieta’s artistic practice. Discussing the absence of the body in the artist’s later works in relation to the Cuban spiritual practices of Santería, Hamilton argues that Mendieta anchors the body’s absence to presence of place, one marked by a history of colonialism, slavery and diasporic culture.

Leon Hsu’s “Queer Identities and Neoliberal Human Capital” analyses how the reality television series Ru Paul’s Drag Race creates a neo-liberal queer self, ripe for capitalist consumption. Hsu argues that celebrity drag transforms the subversive pleasure of ballroom drag “realness” into a gender-conformist product. He concludes by demonstrating how the global reach of queer commodification has altered Samoan Fa’afafine identity from a more fluid conception of gender to "being" trans or gay.

Questions of identity are also at the core of Nic MacMillan’s “Ambiguation,” a short story that creatively responds to gender theorist Jack Halberstam’s proposition that trans life constitutes a remapping and re-embodiment of gender. MacMillan engages with Halberstam’s re-conceptualization of the intersections of self and body to imaginatively speculate on how artificial intelligence experiences gender identity as imposed, limiting, and unsatisfactory.

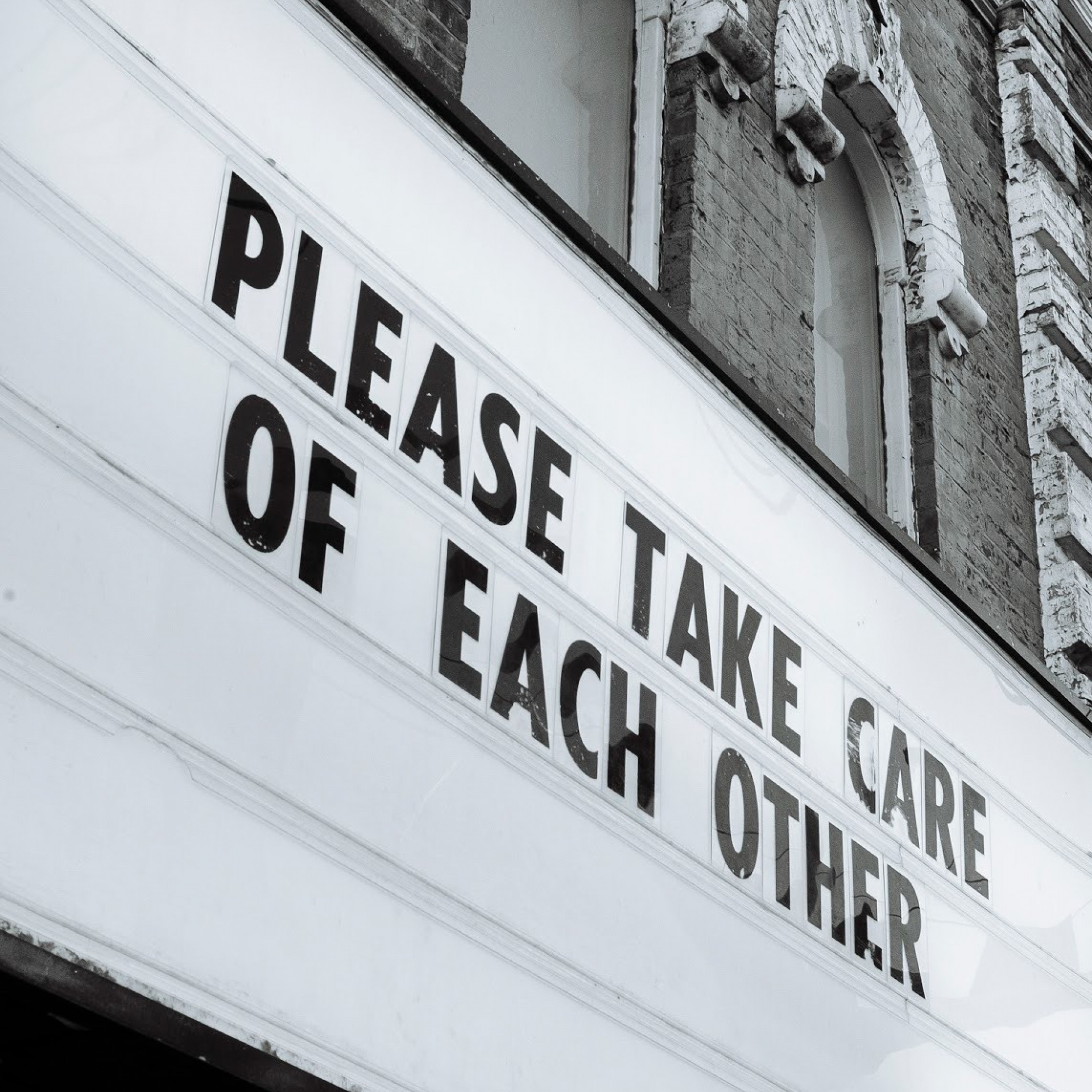

The collaborative photo-essay “Covid-19: Our History Through the Lens,” by Bo Vanderstarren and Malcolm McEwan, directly addresses the onset of the pandemic. Taking to the empty streets of Toronto and Niagra Falls to document the beginning of the lockdown in March 2020, they express through words and images the anxieties of contagion, the strange pleasures of solitude, and the longing for contact and community that permeated the lives of many students during first weeks of the pandemic.

Ada Bierling’s “What is it to Take Care of Each Other?: Oyster Tecture, Companion Species, and Decolonial Animality” closes the section on the body. Casting a critical lens on New York City’s harbour regeneration project Oyster-Texture, Bierling chronicles capitalist consumption and its negative effects on human and non-human bodies. She argues for cross-species collaboration and the necessity of Indigenous philosophies and practices in the ethical realization and decolonization of the harbour regeneration project.

The section on feminist killjoys opens with Aggie Frasunkiewicz’s “Resistance, Recovery, and Memory: A Feminist Reading of Chilean Arpilleras.” This text examines the role of commemoration of the arpilleras, sewn and embroidered artworks portraying the hardships and state terror experienced during Chile’s military dictatorship from 1973-1990. Made collectively by women from impoverished neighbourhoods in Santiago de Chile, the arpilleras narrate resistance to nationalist narratives of oppression and forge memories and future imaginaries of liberation.

Megan Feheley’s “Reflection Paper: gezhizhwazh,” (titled after Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s short story from Islands of Decolonial Love), challenges the assumption that introducing male Indigenous voices sufficiently decolonizes and Indigenizes post-secondary curricula. Feheley proposes that feminist Indigenous voices, like Simpson’s, not only chronicle the effects of colonial power, but, by telling stories of gezhizhwazh—she who overpowers the wiindigo—give strength to Indigenous youth to confront settler and capitalist claims on Indigenous bodies and Land.

Alondra Ruiz-Hernandez’s “Myriad Masculinities in a Patriarchal World” undertakes an analysis of theoretical discourses of misogyny in relation to an auto-ethnography of her experiences working at an all-male summer camp and her visits to a predominantly male public gym. Ruiz-Hernandez challenges dominant perceptions of gender within these sites of collective social organization. Her essay highlights what feels out of place in cultural milieus celebrating childhood and fitness, and reveals their patriarchal, misogynist, and racist underpinnings.

Suhani Karani’s “The Hindu Woman in Love” is a personal reflection on a brief excerpt taken from Simone de Beauvoir’s classic mid-20th century text The Second Sex. Karani engages with Beauvoir’s foundational feminist text to describe how romantic love is deployed by patriarchal power and internalized by women as an instrument of oppression. She argues that Beauvoir's insights on romantic love are reflected in the everyday experience of many contemporary Hindu families.

In a fictional setting of time and place, Erica Jochim's “By Slow Degrees” provides a glimpse of an imagined female painter, Lysbet, living in Amsterdam in the year 1631. Lysbet experiences her exclusion from the patriarchal structures of an art economy through sensing the misrecognitions that underpin a dominant aesthetics of “bouquets of flowers and blocks of cheese.” The creative constraints of her world, seemingly historically distant, invite the reader to recognize the power of the senses in identifying injustice.

Katrina Kuras’s “The Enchantment of Consciousness,” which draws on Lithuanian folklore and the feminist perspectives of Chela Sandoval, closes the section on feminist killjoys. Her short story reimagines the role of the Raganos, village outcasts and healers who dwell at the edges of the forest and bridge animal and human worlds. The main character, a young Ragana girl, Audra, demonstrates the value of all human and non-human life to bring gender equality to village social life.

Through writing the body and feminist killjoys, the twelve texts featured in the first issue of the The Arts & Science Review offer the reader critical perspectives and new possibilities for living in the pandemic world. The texts give shape and voice to diversity, decolonization, resistance to historical and contemporary oppressions and inequities, embracing alternative social and cultural arrangements. As the editorial committee, we found the essays thought-provoking, intellectually and conceptually innovative, and, foremost, a pleasure to read. We anticipate that you as readers will experience your own engagement with the texts in similar and expanded ways.

Kathy Kiloh, Maria-Belén Ordoñez, Dot Tuer

Editorial Committee for the 2020 The Arts & Science Review