Dracula, Jack Halberstam tells us, is a “technology of monstrosity” (88). A horrible and seductive amalgamation of “a wide variety of signifiers of difference” (3), condensing Victorian fears of the other – the other sex, the other race, the other forms of desire – into one deviant body. This body is placed outside the bounds of ‘proper’ and ‘civilized’ society, and is figured as a foreign, sexualized threat to the health and prosperity of Victorian England. I will be exploring the sexual threat in particular here, and the violent, heteropatriarchal punishment thereof. More specifically, I’m interested in the way that the vampire queers the gendered roles of activity and passivity – how women become monstrous in their agency and feminize men in their advances – and how the narrative works to perpetually displace its own homoeroticism.

It is important to place the work within its time – Bram Stoker was writing Dracula at a time in which it was illegal to “promote perverse acts” (Hulan 18). Which is to say, it was illegal to write stories about queer happiness. Sexual and gender transgression must be straightened, through reorientation towards “happy heterosexuality” (Ahmed 90) or punished through death (Hulan 24). Exacerbating this existing threat to queer authors was the sodomy trial of Oscar Wilde, Stoker’s friend and rival (Schaffer 381), and the public’s resulting reactionary homophobia (Schaffer 388). While Wilde was not on trial for his writing, it was still levied against him. The ‘depravity’ of The Picture of Dorian Gray’s titular character was conflated with that of Wilde himself (Hulan 20) – if Dorian Gray is a “sodomite” then so too is Wilde (Hulan 19). This means, in Stoker’s mind, that writers must censor themselves. In “The Censorship of Fiction,” he argues that writers of “filthy and dangerous” works have “brought the evil; on their heads be it” (486). Perceived moral decay, in this writing, is the fault of authors who do no better censor themselves – and so homosexual desire must not be consummated in Dracula, queerness must be condensed into a monstrous form, and that form must be punished. Bram Stoker must bury his gays (Hulan 17), lest he endorse their actions.

In Dracula, interactions between the castle’s vampiric residents and Jonathan Harker quickly establish vampirism as a force that usurps gender conventions – it is, in the language of the time, a force of “inversion”. Queer people were pathologized as neither male nor female, they were of intermediate sex, “inhabiting a no-man's land like the Undead who were neither dead nor alive” (Schaffer 398). Not only are they themselves “inverts”, they “invert” others – Harker, having been rendered the passive and submissive object of desire, later describes himself as having been rendered impotent (Stoker 175) by the experience. He is emasculated by the pursuit of powerful, queer monsters. He even risks death in escaping the castle, which perches atop a cliff, for “At its foot a man may sleep, as a man” (Stoker 53). Unsaid is that, should he remain and fall to the seductions of the vampires, he will be unmanned. And this unmanning will be the result of Harker’s own desire to be penetrated by the three vampire women he calls ‘the weird sisters’ (Stoker 48). These are three women who transgress gender in their agency – they desire Jonathan Harker and so they pursue him. It is their agency and their teeth which figure them as monsters, as both bestow upon them masculine power. The power to take. And Harker yields to this power with horror and longing, “looking out from under [his] eyelashes in an agony of delightful anticipation” (Stoker 38). He is passive, coquettish, prey. At the threat of penetration, he “close[s] [his] eyes in languorous ecstasy and wait[s], wait[s] with beating heart” (Stoker 39). It is only now that Dracula’s desire for Jonathan Harker, which we first glimpse when the latter cuts himself shaving (Stoker 28), is made clear and explicit. Dracula bursts into the room and furiously declares his claim on Harker in an undeniably homoerotic fit of rage: “How dare you touch him, any of you? …This man belongs to me!” (Stoker 39, emphasis added). It is after looking towards Harker’s prone form that he declares “Yes, I too can love” (40). Dracula’s clear, queer desire for Harker is never explicitly stated again – it only exists through the mediating form of a woman – but when he enters England he is queered in other ways.

Dracula, in Jack Halberstam’s words, “condenses… sexual threat into… a body that is noticeably feminized, wildly fertile, and seductively perverse” (89). While Dracula is feminized – exemplified by feeding Mina Harker blood from his chest in a mockery of breastfeeding (Stoker 262) – this is a queer and perverse feminization. It is an agential and monstrous femininity. Jonathan Harker, in that very scene, is rendered a passive and submissive cuckold, as once again a vampiric trance is described in undeniably sexual language: he lays in bed, “his face flushed and breathing heavily” (262). While Dracula’s desire to feed from Jonathan is once again deferred, his desire to possess him remains – “Your girls that you all love are mine already. And through them you and others shall yet be mine” (285). Stoker attempts to repress queer desire by averting homosexual penetration, but it bleeds through explicitly, nonetheless. Dracula possesses Jonathan Harker through his claim on his wife, a claim which threatens to transform her too into an agential feminine monster.

Lucy and Mina, the only two significant woman characters in Dracula, are constantly silenced and therefore rendered passive. On page 123, regarding his treatment for Lucy’s burgeoning vampirism, Van Helsing says, “We must obey, and silence is a part of obedience.” He is reminding her here that her role is to be passive and acquiescent and allow men to do to her what they wish. Similarly, Mina, without whom Dracula could not be stopped, is excluded from discussions to spare her “woman’s heart” (Stoker 219). Mina has read all accounts, has catalogued and compiled all the information, and we are told that is due to her “man’s brain” (Stoker 219) for her knowledge and ability cannot be that of a woman. Her active role in combatting Dracula figures her as a man, and her exclusion and silencing is a reassertion of her rightful place.

It is voicing her desires for agency in marriage (Stoker 58) that renders Lucy monstrous. This is made abundantly clear through juxtaposition with the blood transfusions. In Van Helsing’s words, the transfusion of Arthur’s blood makes Lucy “truly his bride”, but she has received the blood of three others besides, and as a result “this so sweet maid is a polyandrist” (165). Blood, here, is semen (Craft 121). The narrative, however, does not scorn Lucy for the transfusions. They are painted as something born of necessity, something men must do for her. Lucy’s desire to be allowed to marry three men is wrong because it is Lucy’s desire. Four men ‘marrying’ Lucy through transfusions of blood is acceptable because Lucy has no choice – Lucy isn’t even conscious. Lucy is meek and helpless and laying in a drugged stupor while she is penetrated (via needle), and when this penetration cannot save her from the violent, hypersexual masculinization of vampirism, Van Helsing calls for an escalation. "I shall cut off her head and fill her mouth with garlic, and I shall drive a stake through her body" (Stoker 188).

The task of penetration does not fall to Helsing, but to Arthur Holmwood – Lucy’s fiancé. Before addressing this scene, however, those proceeding it must be unpacked, specifically regarding the language used to describe Lucy. In a recurring motif regarding vampires, Lucy is simultaneously dehumanized and unsexed through use of the pronoun ‘it’ (Stoker 188, 197), and hypersexualized through language like “wanton”, “voluptuous” and “carnal” (Stoker 197). The dehumanization of Lucy enables and justifies the violent actions taken against her – in John Seward’s words: “It made me shudder to think of so mutilating the body of the woman whom I had loved. And yet the feeling was not so strong as I had expected. I was, in fact, beginning to shudder at the presence of this being, this Un-Dead, as Van Helsing called it, and to loathe it” (Stoker 188, emphasis added). The “thing” which has occupied Lucy’s body is not Lucy, it is not a person, it is an object (Stoker 199). Interestingly, the agential woman becomes so agential that she is stripped of agency – she is driven by something beyond her, she is not herself, she is a monster fueled by appetite. And women are not allowed to have an appetite. They are not allowed to pursue – to do so is “unholy” (Stoker 200). And so, once again, Lucy must be penetrated as she sleeps, when she is at her most passive.

Under the oversight of Van Helsing, the patriarch, her fiancé takes up the stake and drives it into her chest in a violent caricature of consummation, “driving deeper and deeper the mercy-bearing stake, whilst the blood from the pierced heart welled and spurted up around it” (Stoker 201). It is only after this penetration that Lucy is refigured as herself: “There, in the coffin lay no longer the foul Thing that we had so dreaded and grown to hate … but Lucy as we had seen her in life, with her face of unequalled sweetness and purity” (Stoker 202). She has been corrected and made permanently passive – in fact, it is only now that Van Helsing allows Arthur to kiss her “dead lips… as she would have [him] to, if for her to choose” (Stoker 202, emphasis added). Lucy cannot consent, and it is in this state that kissing her is acceptable, because it is solely on a man’s whim, as is befitting a woman. To quote Christopher Craft: “A woman is better still than mobile, better dead than sexual” (122).

When the stake is understood as a phallic instrument, it is telling who is pacified by it. Which is to say, exclusively women. Alongside Lucy, the three “weird sisters” (Stoker 48) are found, as they rest, “full of life and voluptuous beauty” (Stoker 343) and brutally penetrated by Van Helsing, screeching and writhing before being rendered passive and placid (Stoker 344), put firmly back in their place by a man. Dracula himself, however, is not staked. Dracula is dispatched in a brief description, a handful of lines, by way of knives (350). The homoerotic implications of men penetrating men is once again displaced onto women. Put succinctly by Craft, “In a by now familiar heterosexual mediation, [women receive] the phallic correction that Dracula deserves” (124).

And so, in an expected iteration of ‘bury your gays’, the threat of gender and sexual transgression is neutralized. Queerness is symbolically punished (Hulan 24). Jonathan Harker, now free from the specter of Dracula’s monstrous, perverse desire, and free from his own desire for penetration, has a baby with Mina. Mina who, upon Dracula’s death, has too been liberated from her monstrous potentiality. Queer desires and queer becomings are straightened, reoriented towards the good, correct life of happy heterosexuality (Hulan 17, Ahmed 90), and the queer monster is violently freed from its own aberrant desires.

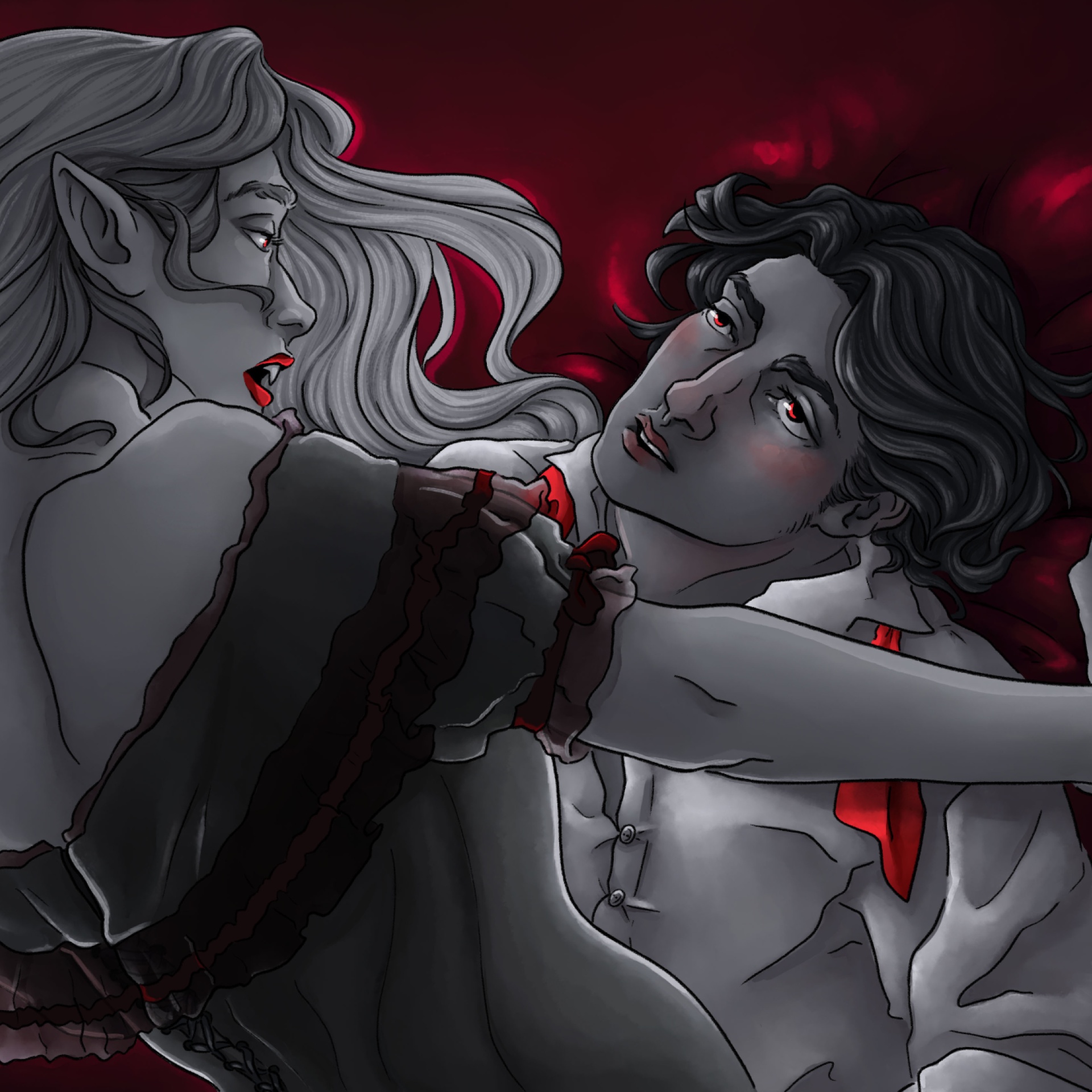

McKenna Pipher

McKenna Pipher is a neurodivergent, queer, nonbinary digital artist and animator interested in gender, sexuality, and in-between spaces. They use variance, liminality and potentiality to queer bodies, places, institutions, and expectations to ask what it means to live in a world, and to interrogate whose stories are valued and told. They are currently working towards their BFA in Digital Painting and Expanded Animation. They live and work on the traditional lands of the Mississaugas of the New Credit, the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee, the Huron-Wendat (Wyandot), the Métis, the Oneida, and the Algonquin peoples. Much of this land is unceded or has been taken by force.

Works Cited

- Ahmed, Sara. "Unhappy Queers." The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press, New York, USA, 2010, pp 88-120.

- Craft, Christopher. “‘Kiss Me with Those Red Lips’: Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” Representations, no. 8, 1984, pp. 107–33, https://doi.org/10.2307/2928560. Accessed 17 Apr. 2022.

- Halberstam, Jack. Skin shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters. Duke University Press Books, 2012.

- Hulan, Haley (2017) "Bury Your Gays: History, Usage, and Context," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 21: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol21/iss1/6

- Schaffer, Talia. “‘A Wilde Desire Took Me’: The Homoerotic History of Dracula.” ELH, vol. 61, no. 2, 1994, pp. 381–425. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2873274.

- Stoker, Bram. Dracula (Oxford World's Classics). Edited by Roger Luckhurst. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Stoker, Bram. "The Censorship of Fiction." Nineteenth Century and After 64 (1908): 479-87.